Breathing in Air, Breathing out Light

Late September 2004

Although nearly October, this is pretty hot to those used to more northern climes. We have decided on a day-trip to Seville. The traffic slows to a crawl as we enter the city on the east-west radial off the A92. It should be possible to get to a cark park right in the middle of where we want to be, by going straight on. There is pandemonium at the critical junction: a police-manned road block - cars stationary at every angle - forces a right onto an inner circular road. The rows of parked police vans are an ominous sign, but of what we are totally ignorant. Entry to the centre is impossible, blocked roads forcing traffic round Seville in circles, at the same time preventing it from getting back to the outskirts. They seem to want us to keep moving until the demo is over.

Surly traffic-police at the diversions refuse to answer our questions, shrugging and waving us on. Grid-lock and car-fumes. Tapas bars in your dreams: there are said to be a thousand - Seville is where they originated. Hopes of ever getting inside one for a cool cerveza are dimming by the minute.

After a desperate detour through side streets, a parking place is found on a orange tree lined street - we walk the kilometre or so back to the Paza de Triufo passing the ancient Jewish quarter and a group of protesters in their white union T-shirts. It is a national dockers strike: the authorities seem bent on protecting government buildings. This is the country of the Basque separatist terrorists, ETA.

George Gordon, Lord Byron, wrote: "A pleasant city famous for its oranges and women.." Even today, lungs full of exhaust fumes, difficult to disagree with, though after a day trip taking in the Gothic Cathedral and the Alacazar, this is not the outstanding impression left from an all-to-short visit to a vast city, viewed to perfection from the viewing gallery high up in the 96 - some say 98 - metre high Giralda tower. This works out at roughly 290 feet, though the viewing galley is at just over 200 feet above a low-rise city spread across the Rio Guadalquivir, which tips itself into the Atlantic at Salucar, into the very same waters Nelson's fleet patrolled three hundred years ago. 80 kilometres south is Cabo de Trafalgar. A similar distance further on, Gibralter,a port he probably used, ceded to Britain at The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht.

But this is not an encomium to British naval achievements: rather a paeon of praise to cultures learnt about in detail, on the ground, for the first time. It is not oranges or beautiful girls that an experience of Spain's once capital leaves in the mind and heart, but rich, diverse, complex, intermeshed sets of cultural influences. Even sitting back home, later, with maps, guide books, photographs, notes and those special recent memories that are still more perception than cognition, the heart-stopping grandeur, power, majesty of the two Spanish cultures - Islam and Christianity - are there in the minds' eye: represented by the cathedral, with the famous Geralda Tower once minaret, and the Alcazar with its dazzling courtyards and gardens.

The cathedral was visited first. A demonstration of the resurgent power of Christian Spain if ever there was one: Fernando III reconquered Seville in 1248. The Almohad mosque, which stood there before it, reconsecrated and used as a Christian church, surviving as such till 1402, then demolished to be replaced by the largest Gothic church in the world. The guide books tell us the outline of the two superimpose quite closely.

The minaret was originally crowned with four large golden balls which were said to be seen from more than 40 Kilometres away. When the Muslims surrended the city they asked for permission to destroy the tower. Prince Don Alfonso replied with the now famous: "If only one brick were removed from the tower they would all be stabbed to death."

The top of the Giralda is reached by a 35 ramps rather than steps: it is said the muezzin in charge of calling the people to prayer climbed to the top on his horse. I'd like to have seen him on the descent! The tower as it stands today is higher than it stood as a minaret: between 1558-68, as the city became rich with American gold, the church authorities decided to build a new top as a symbol of christian power. A Renaissance-style belfy was added to the Islamic body. Finally, a weather vane in the shape of a woman, the Giraldillo, was added, symbolising faith.

Inside the cathedral: a pair of central pillars, nearest the entrance, clad in massive, circular steel clamps running from tip to toe. A modern engineering feat few of the tourists even looked at as they shuffled into the darkness to marvel at the height of the ceiling. Was the building weakening because of lack of flying butresses? From the top of the Geralda, later, it was possible to look down on the complex set of interwoven butresses running off each side of what amounts to an equal-sided cross. A careful examination of an aerial-view postcard of the cathedral showed buttresses crossing one or two others at 90 degrees, while others at the edges stood alone.

This is a very big church. Its proper title is Catedral Santa Maria de la Sede. Its size is trumpeted with impressive dimensions: 126 metres (413 feet) long , by 83 metres ( 272 feet) wide by 30 metres (100 feet) high. Santa Maria has the largest interior in the world and is the third largest cathedral behind St. Peter's in Rome and St. Paul's in London.

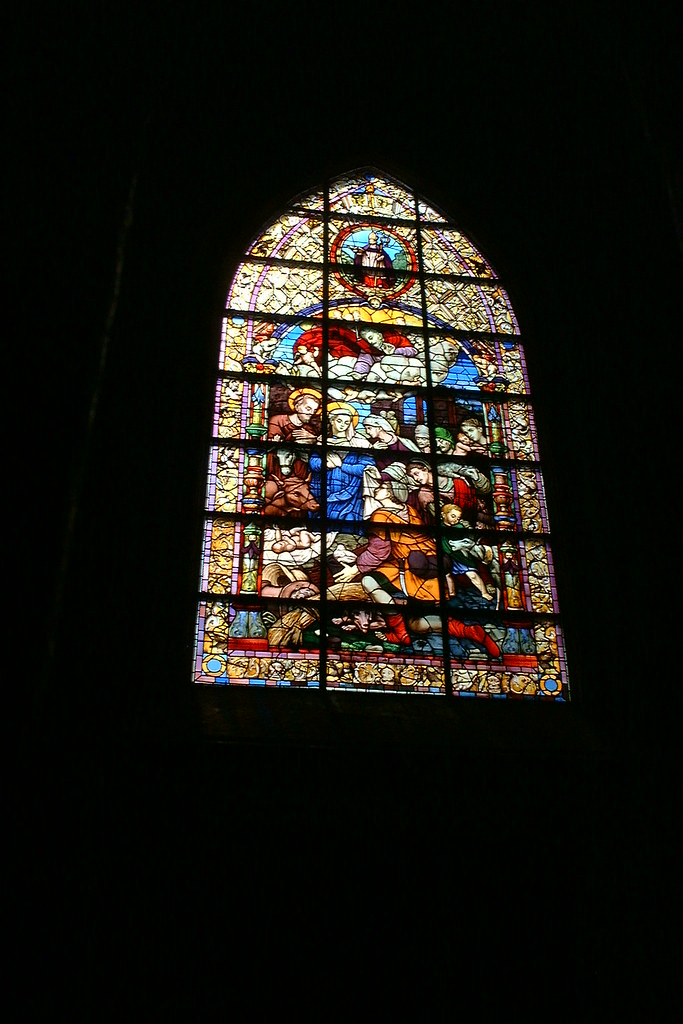

I like going into Churches, but they don't hold me for long. This interior - with its massive golden altar screen, 19 century all-wood mausoleum where the remains of Christopher Columbus are said to rest (startling as you stand there even if not true), and galleries of important Renaissance religious art - is no exception. The dark oppressiveness gets to the non-believer. No Reformation stained-glass window smashing here, to shed light on the matter. But then none of these artifacts would look good in bright light.

A short walk across the square to the Alcazar: a journey from darkness to light. I remembered a writer about East Africa who said the experience of a particular tribe was like 'breathing in air and breathing out light'.

Abd Al Raman ordered the construction of this fortified palace in 931 AD. In the space of minutes and a few hundred paces, a miraculous emotional and psychological transformation: entering the first courtyard an immediate feeling of something extra-special. The claustrophobic gloom of the Cathedral has been completely forgotten, replaced by a 'lightness of being': openness and optimism, a realisation there will not be enough time to appreciate it all; promises, before it has been properly seen, to come back for a better look.

The cathedral: power and majesty; the Alaczar: power and intimacy.

A living space, this, not a worshipping one. Its design, in gross terms, reflects the requirements of life in a very hot country: water, coolth and shade. Walking through corridors or vestibules - often following right-angles to hide the view into inner courtyards that they lead to - it is obvious the whole edifice has been cleverly arranged to create cool air currents: hot air from outside sucked cunningly through passages into shady rooms, puffed out, still cool, into sunny open spaces: a system a physics teacher would delight in explaining. The Islamic architectural embellishments are impressive, but as nothing compared to the irremovable impression that these people, a thousand years ago, whoever they were, knew how to build a perfect living-place.

Seville:wiki

1 Comments:

Our first contact with a blog. Thanks for the magnificent report!

RP

Post a Comment

<< Home